Typing is a headache

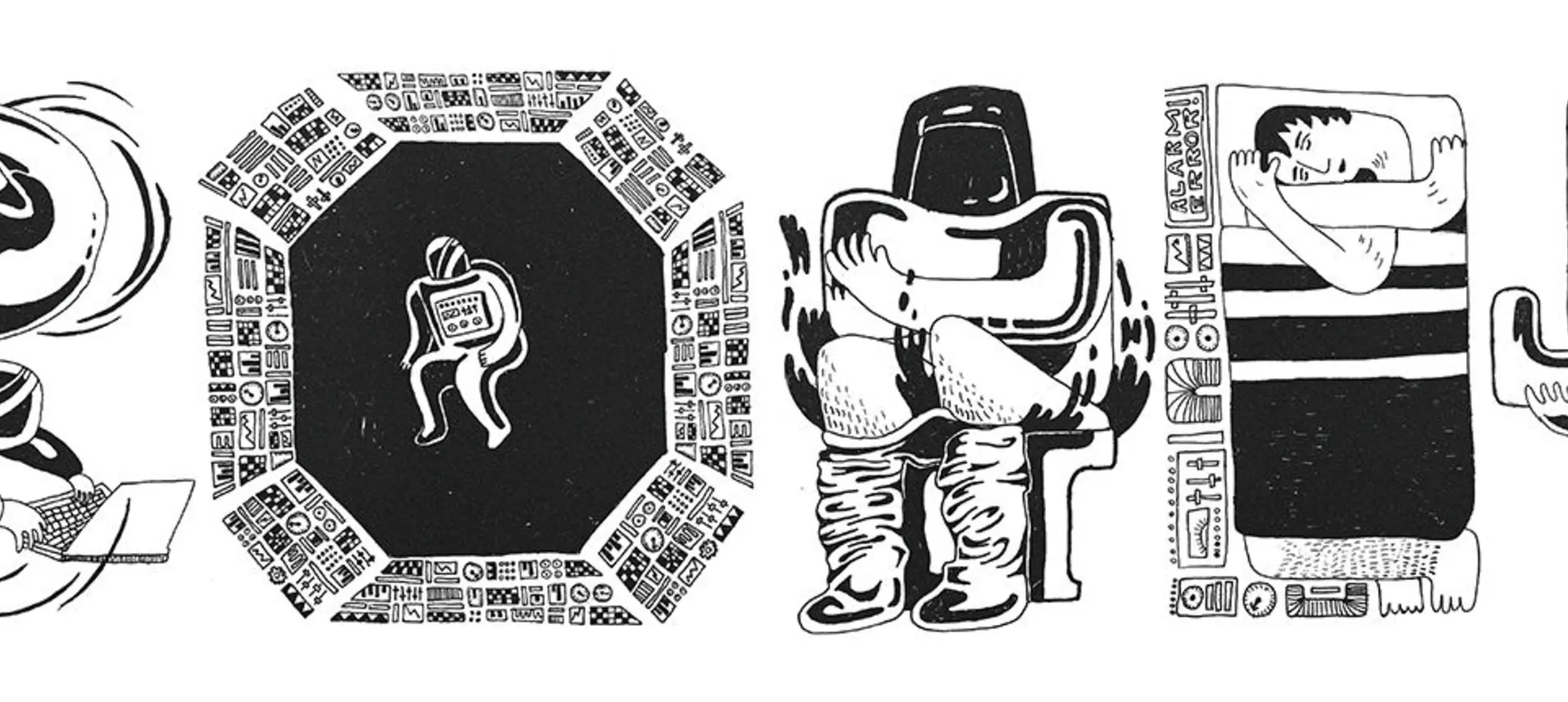

A major source of annoyance is the weightlessness resulting from the International Space Station’s (ISS) constant state of free-fall. In the microgravity environment aboard the ISS, everything behaves differently and Newton’s law about equal and opposite reactions can be a real pain. When astronauts write messages home or enter data, they have to be sure to Velcro their laptops to a nearby wall and their feet to another; otherwise they will float gently away from their keyboards with every keystroke.

Even breathing gets complicated. Without gravity to pull exhaled carbon dioxide down and away from their heads, astronauts can experience carbon dioxide headaches if they don’t move around enough and disturb the bubble of exhaled air that forms around their heads. Even if they spend all day moving, the air filtration system aboard the station can only scrub so much carbon dioxide and in any given week there is at least a 1% chance that someone aboard will have a headache.

Why bother?

And it’s not just the relentless schedule downloaded from mission control that you have to get used to if you want to be an astronaut. Life aboard the ISS is much like life with five flatmates, except that on station, there is no leaving the flat. Astronauts live for months at a time cooped up in close quarters, working in stressful situations. The constant hum of the air circulation, electrical and heat systems mean that even when the astronauts get into their sleep pods and close their eyes, there is no peace and quiet. Add to this the frustration that must come with knowing that even though they spend hours exercising every day, they still won’t be able to stand for a few weeks when they return to Earth.

And despite all of these out-of-this-world problems, we still go to space. Why? For science, to fulfil the human desire for discovery and exploration, and a little bit because of the view.

Get me a napkin, quick!

It also turns out that a lack of gravity makes ‘spending a penny’ more difficult. While the ISS has an advanced vacuum-style lavatory, the early Apollo astronauts were less fortunate. They had little more than a plastic bag and some duct tape. Thinking the procedure was straightforward, one foolhardy astronaut forwent reading the instructions and the following sentenced was uttered, recorded, and will go down in the annals of spaceflight: "Get me a napkin quick. There's a turd floating through the air."

Lost in (a small) space

Weightlessness isn’t all bad though. Aside from often being described as fun, it can also make for some pretty entertaining pranks. When the Japanese Kibo module was installed on the ISS, the astronauts quickly discovered that the distance between walls was such that if a colleague was placed carefully in the centre, they could not escape except by swimming through the air:

When astronauts have to leave their spacecraft, they get into a smaller, body-sized one called an Extravehicular Mobility Unit (EMU) or an Orlan suit if they’re Russian. While these suits protect astronauts from the harsh environment of outer space, there is no way to scratch itches. And don’t even think about sneezing in one. If astronauts absolutely have to sneeze they are trained to do it downwards into their collars because there aren’t any windscreen wipers on the inside of the helmet.

When you’re living in space, there’s a lot that can go wrong. Of course, there’s the big stuff, like a micrometeorite strike that punches a hole in the station, or a glitch that makes the life support system malfunction. But mission control has written plans and the astronauts have trained for thousands of hours so everyone knows what to do in the event of a catastrophe.

Every space shuttle since the Columbia incident even had a backup shuttle ready for launch in case the crew needed rescuing. Space is a dangerous place, and everyone knows it. What people hear less about is that space can also be really annoying.

If you’ve ever heard of first world problems, these are out-of-this-world problems.

Written by CHRISTMAS LECTURES Assistant Jon Farrow. Illustrations and text copyright Royal Institution.