Since its foundation in 1799, the Royal Institution's (Ri) guiding aim has been to report, communicate, and display developments and innovations “for the common purposes of life.“ From 1799 and throughout the nineteenth century, this covered the arts as well as natural sciences.

Throughout history, the Ri has attracted the most talented thinkers of the day and played host to a wealth of lectures related to art, literature, music, heritage and more!

Many of the artists and scientists who share connections with Ri have made significant contributions to how we understand the world around us. One of the most influential figures was chemist Humphry Davy, who became the first Director of the Laboratory. Davy was a pioneer of electrochemistry here at the Ri, where he successfully isolated several new chemical elements, including magnesium, calcium, barium, and strontium. As a self-taught chemist and inventor, he was a huge inspiration for aspiring young scientists, such as Michael Faraday.

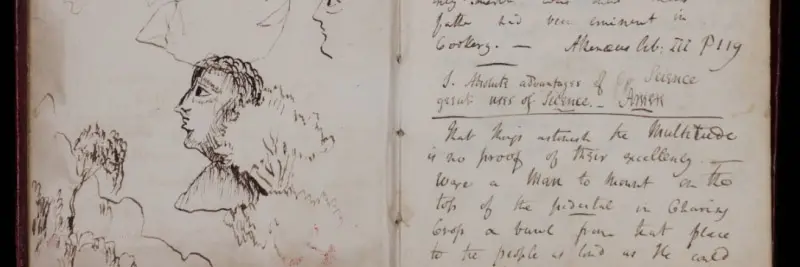

What is less well-known today is that Davy was also a prolific poet. Not only did he fill his scientific notebooks with lines of verse and publish his own books, but he also edited some works of the renowned Romantic poet William Wordsworth. Researchers who have spent time close-reading Davy’s poetry have found that it offers fascinating insights into the chemist’s mind and his scientific breakthroughs. You can find out more about the Davy Notebooks project here.

The Science of Poetry

Today, the arts and sciences are often viewed as separate fields. But Davy’s notebooks and the Ri’s long list of lectures that have taken place since 1799 show us that this line was much more blurred in the past. During the Romantic period (an artistic and intellectual movement that began around 1798 and lasted until 1837), establishments like the Ri provided spaces where scientists, writers, and artists could learn about the latest innovations and new knowledge.

Romantic poets such as Samuel Taylor Coleridge, William Wordsworth, and the Poet Laureate Robert Southey were among Davy’s good friends.

The arts inspired scientists to approach the material world in new ways. Poets and painters also found scientific experimentation and innovations interesting. For example, Wordsworth wrote in the Advertisement to his influential collection of poetry, Lyrical Ballads (published in 1798), that his poems were to be viewed as “experiments”. This is one of the first instances where the word “experiment” was used to describe an artistic practice.

John Constable’s Experiments with Painting

Another well-known Romantic figure who was a member and lecturer at the Ri was the British landscape painter John Constable. His most celebrated artworks are his “six-footers”, which are a series of famous six-foot landscape paintings. These include The Hay Wain (1821) and Salisbury Cathedral From the Meadows (1831). As these artworks show, Constable loved to paint scenes from his childhood home in Dedham Vale, Suffolk. In fact, his picturesque paintings became so iconic that the region was commonly described as “Constable Country”.

Constable preferred to paint his pictures outdoors and drawing from nature. An excellent example of this practice can be seen in his cloud study period of 1821-1822, when he made around a hundred studies of clouds from Hampstead Heath. This practice of drawing directly from nature and then later in his career transferring his observations onto the large canvases of his six-foot landscapes revolutionised landscape painting. As a result, the painter played a key role in elevating the landscape genre within the Fine Arts.

In 1836, Constable gave a series of lectures on landscape here at the Ri, which would be some of his last lectures before he died. During one of these events, Constable stated that, “Painting is a science and should be pursued as an inquiry into the laws of nature.” He encouraged the audience to compare the approach of the artist, who closely observed and painted the landscape, to that a scientist. To conclude, he asked the audience,

"Why, may not landscape painting be considered a branch of natural philosophy, of which pictures are but the experiments"?

Wordsworth was sitting there in the audience that day, much to Constable’s delight, who was an admirer of the renowned poet. As a sign of his admiration, Constable gifted the poet a book of engravings made after his pictures. But there was another famous innovator also in attendance at this important lecture: Michael Faraday.

The presence of such a prestigious scientist at Constable’s lecture shows us that the collaborative sharing of knowledge and ideas across disciplines has been an important principle of the Ri since the early days. It also serves as an important reminder that the boundaries between the arts and the sciences is perhaps not so defined as we tend to believe.

About the author

Kate Nankervis is a PhD Researcher at the University of York looking at clouds in Romantic period poetry and landscape painting.

Her research examines clouds as a way into identifying a new mode of ecological consciousness in the early-nineteenth century, which is linked to contemporary climatic changes and the new science of meteorology. She recently completed a 3-month internship at the Ri about science communication.

She can be found on Bluesky at @womanofclouds.bsky.social