The Royal Institution's CHRISTMAS LECTURES are the highlight of the festive programming season, but this wasn't always the case. On the 100th anniversary of the first public television demonstration, it's worth remembering just how uncertain (and unlikely) the partnership between science and the small screen once seemed.

An Attic on Frith Street

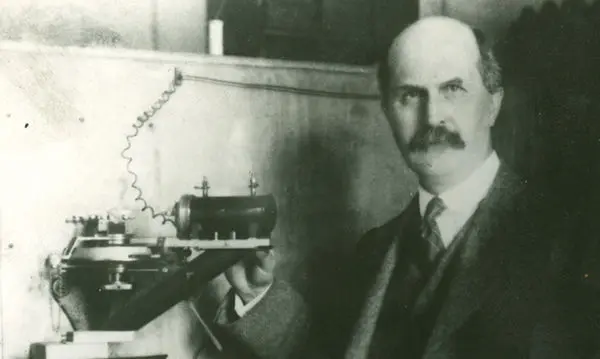

One hundred years ago today, on the 26th January 1926, members of the Royal Institution (Ri), and its Davy-Faraday Research Laboratory made the short walk over to Frith Street in Soho. Inside inventor John Logie Baird’s laboratory-attic, they witnessed a new technology: television. As grainy images were transmitted from one room to a small screen in the next, it's unlikely that anyone could have imagined that transmitted images would transform how the Ri would share science with the world.

At this time, the Ri’s relationship with the public was already expanding. A few years earlier, in the audience of the Ri’s 1923 CHRISTMAS LECTURES was John Reith, who had just become General Manager of the fledgling British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC). Watching then Director William Henry Bragg captivate his audience with demonstrations, Reith saw an opportunity. Just weeks later, he approached Bragg about broadcasting something on science over another medium: radio.

An Interesting Experiment

Bragg's radio series, adaptations of his CHRISTMAS LECTURES, established a partnership between the Ri and the BBC. But radio had one obvious limitation for an institution built on visual demonstration. When Cecil Lewis, one of the BBC's original trio, approached Bragg in late 1936 about a short television slot on the new television service, Bragg accepted.

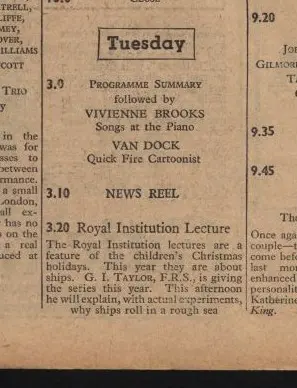

Just six weeks after television broadcasting launched in Britain, a fifteen-minute preview of that year's CHRISTMAS LECTURES went out not from the Ri's theatre, but from Alexandra Palace. G.I. Taylor, an applied mathematician, used experiments to show how ships move through water and how waves form. Ahead of the broadcast, Bragg commented that Taylor was "a little doubtful which experiment, if any, will lend itself well to television." (BBC Written Archives Centre) In 1936, no one quite knew how scientific demonstrations would translate to this strange new medium.

It was the BBC's first scientific broadcast, but those early experiments were just that—experiments. For the next two decades, the relationship between the Ri and the BBC went through a rocky period, and only occasional CHRISTMAS LECTURES were broadcast.

Finding the Right Formula

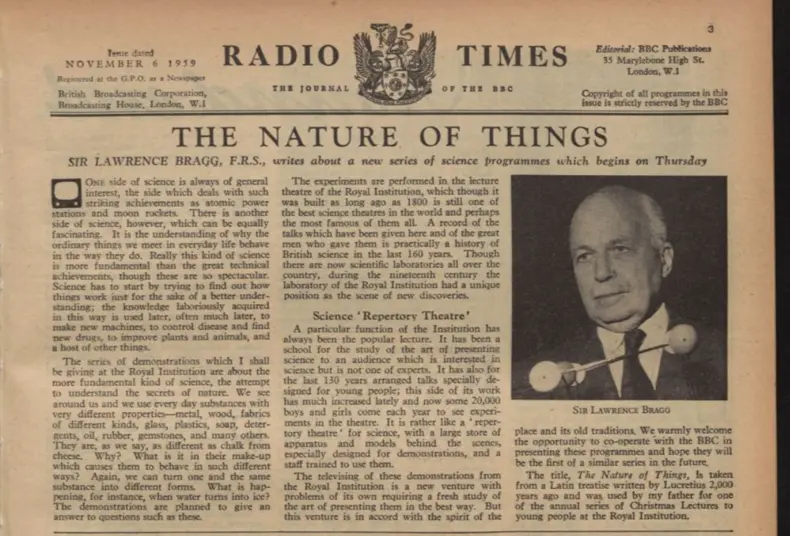

All this was to change when William Henry Bragg's son, Lawrence, became Director in 1954. Rather than televising the CHRISTMAS LECTURES, in 1959 he pitched "The Nature of Things" to the BBC, a reimagining of his father's CHRISTMAS LECTURES. The BBC recorded the series on site in the Ri's theatre, filling it with members and their children.

Whilst it was generally well received, not everyone was convinced. One viewer complained to the BBC that the Ri audience was applauding too enthusiastically after each demonstration. The relationship between the theatre audience and viewers at home was still being negotiated, and the Ri's theatrical customs didn't always translate well to the small screen. Still, the series proved something crucial: there was an audience at home for science, and this format could work.

1966: Live from Albermarle Street: It’s The CHRISTMAS LECTURES

In 1966, as Lawrence Bragg handed over the directorship to George Porter, the BBC was ready to take the plunge: for the first time, all the CHRISTMAS LECTURES would be transmitted live, in full, from Albemarle Street. The Ri chose Eric Laithwaite to be that year's lecturer, the Lancastrian inventor of the linear induction motor. Laithwaite's year of planning established the modern era of the lectures.

But live television presented unique challenges. The Ri's theatre is an intimate space, much smaller than it appears on screen. Clever camera work creates the illusion of a grand lecture room, but in reality, negotiating large television equipment in such a compact Georgian theatre was no easy task. Camera operators, sound technicians, and the Ri's demonstration team had to work in careful choreography, all while keeping the magic alive for both the theatre audience and viewers at home.

When Science Meets TV Magic

The other challenge was more fundamental: while the essence of scientific experiment is that things can and do go wrong, television audiences expect things to work. Behind the scenes, it often fell to Bill Coates, the legendary lecture demonstration technician, to bridge the gap between reality and television expectations. Coates worked on perfecting demonstrations year-round, thinking not just about whether an experiment would work, but whether it would work on camera and whether it could be reset quickly between takes. On occasion, he had to be particularly creative to ensure things appeared to work smoothly. This was the delicate balance: maintaining scientific integrity while meeting television's demands for reliability and polish.

Coates became something of an unexpected cult celebrity in the process. His ingenuity represented the Ri's commitment to making television work while staying true to the spirit of hands-on science demonstration.

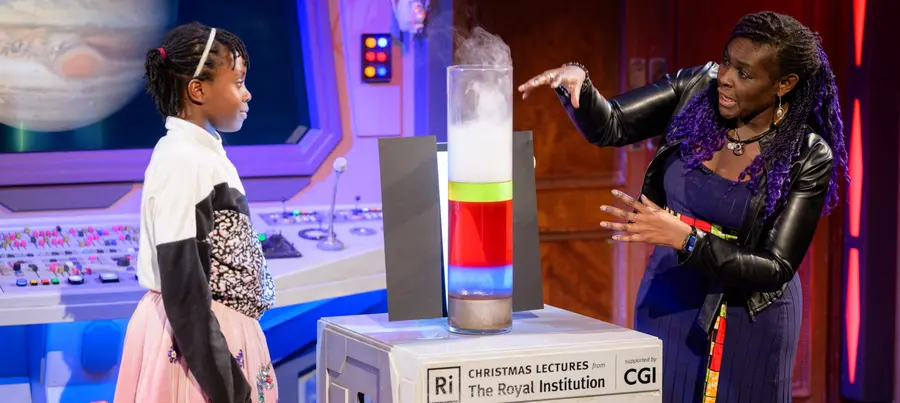

The move away from live broadcasting in later years brought both losses and gains. Pre-recording enabled messier, more ambitious demonstrations, experiments with precise timing, elaborate setups that transformed the theatre, and the freedom to stop and reset when needed. As television and its audiences have evolved, the format reduced from six lectures to three, but the topics expanded dramatically. Under Porter, the Ri also broadcast other shows, such as "Controversy" (1971-1975), and the occasional Friday Evening Discourse, but it was the CHRISTMAS LECTURES that endured as the Ri's signature television presence.

An Indispensable Tradition

Today, the queue of excited families still snakes around 21 Albemarle Street each December, but our reach has never been greater. The Ri now livestreams the CHRISTMAS LECTURES at venues across the UK, letting more people see the lectures, clean up and all. You can also find the CHRISTMAS LECTURES archive on demand through the Ri's website, and all our talks on YouTube, accessible to anyone, anywhere in the world.

From the first glimpses on Frith Street a century ago to today's global digital audiences, the Ri has continually adapted to new technologies while following its mission of making science accessible to all. Back in 1936, G.I. Taylor could not have even imagined that his first cousin twice removed Geoffrey Hinton, would now have a lecture on our Youtube Channel that you can watch anytime, from anywhere in the world.

The Ri has just marked 200 years of the CHRISTMAS LECTURES, and this centenary of public television reminds us how far we've come. One hundred years ago, those scientists walked back to the Ri from Frith Street having glimpsed the future. Today, television allows millions to the connect with wonders of science, broadcast from the very same theatre where it all began.