‘We are all very thrilled at the prospect of going out of course, but it is jolly rotten for Mother.’

The First World War is falling out of living memory. We have the stories of the terrible conditions in the trenches, the battles fought and the huge loss of life but somehow the very scale of it makes it hard to comprehend. It helps to remember that history isn't just about the broader picture but is made up of the actions of individual people, and often their stories are the most immediate and interesting to tell.

I've been looking at the family correspondence of the Bragg family for the First World War period in the archives of the Royal Institution, it includes poignant letters from Robert Charles (‘Bob’) written to his family and particularly to his mother, Gwendoline, to whom he was very close. Robert was one of the thousands of young men who lost their lives at Gallipoli; he lasted less than a month on the peninsula, killed by a direct hit on his battery dugout about ten weeks before his 23rd birthday. This was 1915 — the same year William and Lawrence Bragg, Robert’s father and brother, were jointly awarded the Nobel Prize for Physics, altering the fortunes of the family and ultimately the reason why some of their letters are in the Ri archives to be read.

Reading someone’s letters, no matter if the writer is long dead, is a strangely intimate experience. You feel as though you’re getting to know them, seeing a face they showed to only a few people in their lifetime, which makes it all the more jarring when little details stand out which remind you that they were written almost exactly a century ago.

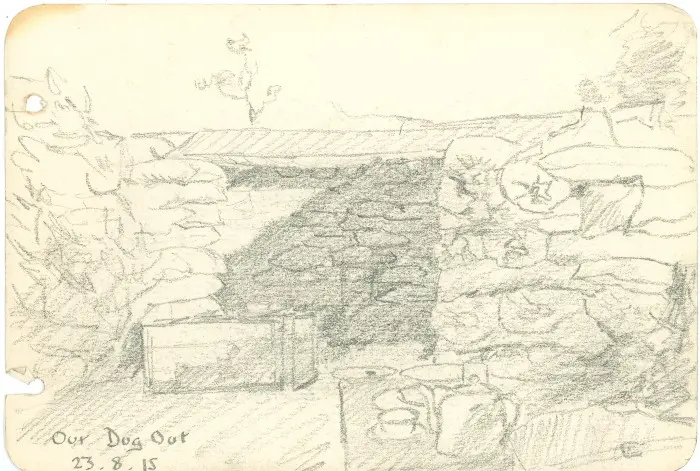

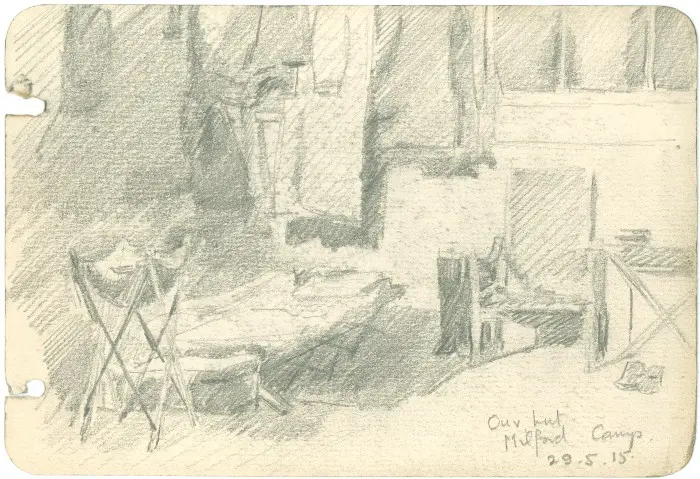

We have no letters written by Gwendoline but through the letters sent to her a picture forms not just of the conditions of the war, but of family dynamics in a time of turmoil. While Robert often glosses over the horrors and hardships of the front, his character comes through strongly in the letters, optimistic and interested in the places he finds himself. Through his descriptions and the few sketches he made we can see Gallipoli through his eyes.

It would be best to let his letters tell their own story but when I transcribed the letters in the collection I found it was more of a book than an article. I’ve instead tried to tell the story with a handful of quotes and a few longer extracts.

‘It is simply ripping having all the riding lessons instead of parades in the morning.’

In November 1914 Robert, previously training with the King Edward’s Horse Special Reservists, applied for a commission to the Royal Field Artillery. After about seven months training he was finally sent out on active service as part of the 58th Brigade R.F.A. His initial letters are written with boyish enthusiasm, detailing the minutiae of every-day life and the relative tranquility of the early stage of training. He is concerned with getting kit together, and enlists his parents help to find everything from underpants to a service revolver.

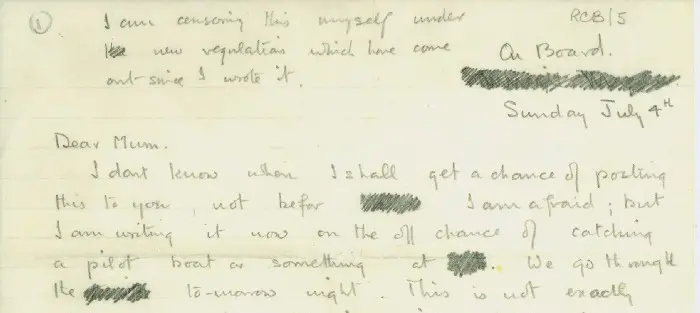

‘I am censoring this myself under new regulations which have come out since I wrote it’

Once he ships out the tone begins to change: he’s travelling into the unknown and constantly encountering new situations, but has also been put in charge of censoring letters and is very aware of not sharing sensitive information, even with his mother. His first letter on ship shows evidence of this. He has to scribble out several words to meet regulations, after this he starts to self-censor as he writes: ‘We pass all kinds of interesting things I wish I could give you details of them all. I will some day’ It must have been frustrating and somewhat isolating not being able to describe all the new places and things he experiences in proper detail to his family and close friends.

The ultimate destination of the Brigade was Gallipoli, but they were held first in Alexandria and then Lemnos as troops gathered for the next wave of the campaign. Through the journey heat was a huge problem, but once on land Robert is typically optimistic. ‘This climate is going to rather suit me I think.’

His letters are still generally enthusiastic but where a letter took a day or so to arrive when he was training in England, there is now a delay — in both directions — of some weeks and this has an effect on his mood. If this is something I can pick up I wonder what Gwendoline would have thought, reading between the lines. It is clear that what he really wants is to know what’s happening to the rest of his family: today it’s hard to imagine having to wait so long for news, especially during war time.

At Anchor

August 4 1915

Dear Mum

I have just heard that the mail bag closes to-night so I must hurry up & get off a letter off to you. We had a very comfy trip over from Alexandria and for the last four days we have been lying at anchor in this harbour, thoroughly enjoying ourselves. Unfortunately there isn’t much tide here so the harbour is pretty foul as it is absolutely crammed with shipping. However we lump it & bathe with great vigour. It has been awfully jolly having these few days with absolutely nothing to do. …

…We took out one of the life boats today & tried to row to some place where the water was moderately clean. We got some good exercise & a bathe, but no clean water though we went far enough in all conscience. What is Bill doing now. I wrote to Bill last mail, I don’t know whether he got it or not. We have only had one mail so far. I wish we could get another, there is a chance of one coming along with our horses. It’s a perfectly glorious evening, the sun has just set just like it did in Australia & now there are only cool shadows, with a dead flat & oily sea & pale blue hills, very broken, in the distance.

Now I must stop as I have to censor a large pile of letters befor[e] mine.

Cheer Oh.

Your loving Son, Bob

Reading through the letters you see Robert’s experiences through Gwendoline’s eyes. It must have been terribly worrying, especially as things went very quiet after this letter: Robert was sent on to Gallipoli a few days later as part of the August Offensive, the last major attempt to take the peninsular. The landings began on the 6 August, Robert landed on the 9th but didn’t have time to write anything until the 18th.

But before those letters even arrived, Gwendoline received a telegram from the War Office on 1 September stating that Robert has been severely wounded. More news to follow. Two days later an official telegram to confirm that he had died aboard the hospital ship Nevasa.

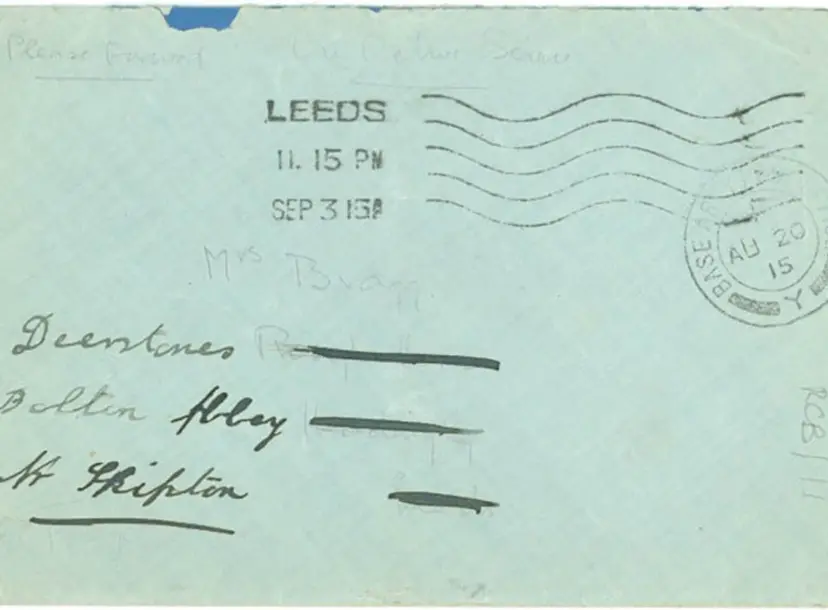

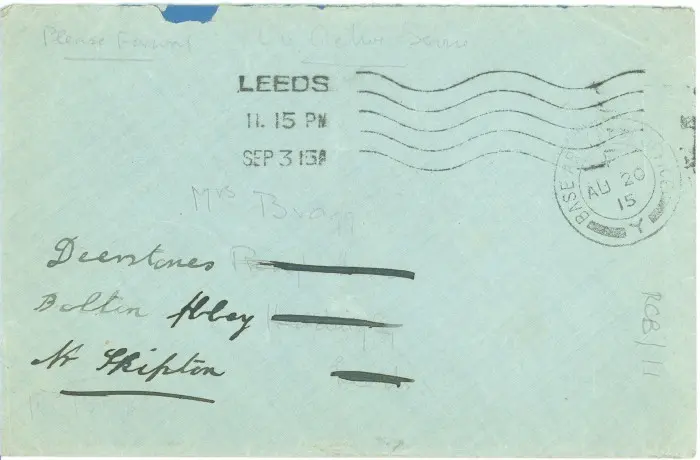

The overseas letters all still have their envelopes, their journey home recorded in a series of stamps. It wasn’t until I was reading back through the letters that I noticed that Robert’s first letter from Gallipoli is post marked the same day as the second telegram. It seems terribly cruel that letters from Robert continued to arrive throughout September, echoes of a life already lost.

In his first letter after landing, Robert summarises the chaotic events so far. He skims details, either so as not to worry his mother or lack of time. Despite his brevity, it is clear that it’s been a frustrating and tiring experience.

Letter 11. Robert to Gwendoline Bragg. 18 August 1915

Battery “Dug Out”

18 August (I think)

My Dearest Mum

At last I have a chance to write you a line. I am afraid that there is a long gap between this & my last letter posted at M[o]udros just before we left. Well Mum dear the last few days have been the most strenuous I have ever had in all my life. The infantry landed befor[e] us & we watched from the harbour. They just landed & walked on with very little opposition at first. We landed two or three days later in small batches.

Things were in a frightful mess they landed our guns in one place our horses in another & our men in another. Consequently it took some time straightening up things. The country here is hopeless for moving guns over, no roads but sandy tracks, and all the rest is boulders & prickly shrubs but there is one thing in its favour, the climate, at least at present, is glorious, day after day its just the same, not unbearably hot in the middle of the day & cool at night. There is a rainey season though I think when it pours torrents all night & all day.

Well Mum things aren't moving as fast as I expected though we seem to have taken up enough different positions in the last few days to last us for a lifetime. We were shelled out yesterday & so last night we moved & I hope there will be peace for a little. We have at last got hold of our mess list & to-day have fared like lords. For the first week we lived on Bully Beef biscuits & water, not too thrilling. I have just got hold of that box of chocolate etc you sent to Witley I have been saving it up for some auspicious moment & the joy of that chocolate was past belief!

War is a frightfully tiring sort of game, you shoot all day & move guns & dig all night until you are so tired, that your knees literally knock. The Turks shells aren't much good, one burst just over me when I was crossing the open the other day & churned up the dust all around me but nothing struck me, which was rather luck. Also their H.E is rotten, one landed a 6” one landed about 3 yds from one of my guns yesterday & did nothing. The snipers are jolly bad, they paint themselves green & hide in trees & bushes & have a pot at you as you go past.

I nearly went to sleep just then. We have been told that there is a chance of a peaceful day to-day so the Major is sending down half the Battery down to bathe. I haven’t had my clothes off since I landed & I can tell you they want changing. Well Cheero I am going to snatch a few hours sleep to make up for the many nights out of bed. I am feeling awfully fit but longing to get back nor am I the only one.

My best love to you and Dad,

Your loving Son

Bob

There are a further three letters from Gallipoli, all generally cheerful in tone. Reading these letters I’m aware that when they were read is just as important as when and where they were written; it must have been dreadful for Gwendoline to receive them.

While it’s clear that Robert was having an easy time of it compared to the infantry divisions he does spend quite a bit of time downplaying the danger, especially in the letters to Gwendoline, describing the bad ammunition and the lack of range of the enemy artillery. The telegram notifications had very little information about the circumstances of Robert’s death, it is not until several days later that they received details from a friend of his in the Battery and the sad irony of the situation is made clear.

‘…mere words are utterly too feeble to express my feelings of sympathy at your great loss.’

A Battery Dug-out, 6 September

Dear Mrs Bragg

It is with the deepest regret that I sit down to write this letter — I feel that mere words are utterly too feeble to express my feelings of sympathy at your great loss.

It was a most un-fortunate accident, as your Son & Ellison were sitting in our Dug-out censoring letters when a shell came through the sand-bags severing your Son’s left leg & injuring the other to such an extent that it would ever have been useless — - Ellison escaped with a slight wound on his elbow -

Your son was immediately taken down to hospital and expired on board a hospital ship early next morning.

As his constant companion for nearly a year I am proud to think that we had made a lasting friendship, I cannot tell you how he will be missed as the best of good comrades –

Yours deeply sympathising

R. H. Peel

This article was written in 2015 by Jane Harrison, who was Documentation Manager at the Ri

Further reading

- The Bragg film archive provides historical, scientific and personal insights into the work of father and son William and Lawrence Bragg. Many videos are available on our Archive YouTube Channel

- Find it in our museum: William Bragg's spectrometer

- History of William Lawrence Bragg and William Henry Bragg at the Royal Institution