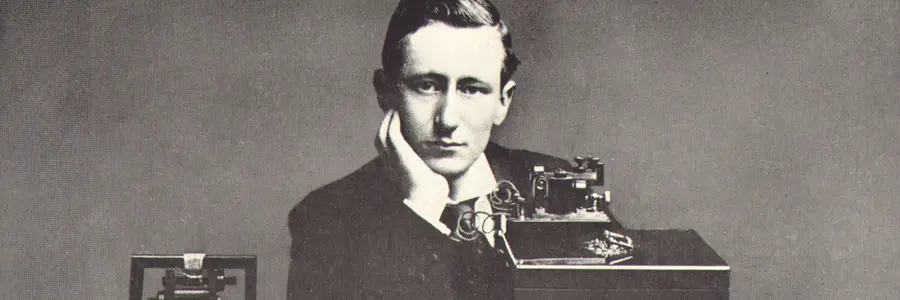

It’s shortly before 9.00pm on 12 June 1903, and wireless pioneer Guglielmo Marconi is hunched over his ground-breaking long-range wireless transmitter in Cornwall, about to send a special message to the world. Two hundred-odd miles away, a packed audience in the Ri Theatre in central London waits in excited anticipation for Marconi’s message to arrive.

And arrive it did. But not before an earlier message had been received, one that nobody had been expecting.

Marconi’s supposedly secure wireless system had fallen prey to the first known and recorded act of public hacking.

"To hack" is to cut with rough/heavy blows or to gain unauthorised access to data in a system or computer. For most people, ‘hacking’ automatically generates a negative response, a modern phenomenon that usually includes celebrities, banking or email data. But for as long as there have been developments in technology, there have been people around to test for weaknesses or come up with improvements. It was long-seen as a duty of care in order to not let the public be fooled.

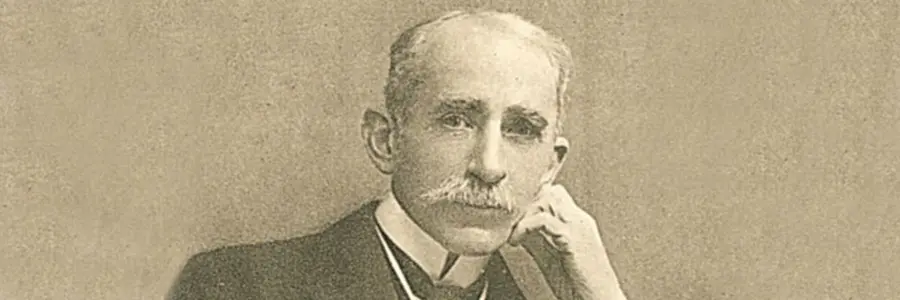

And so it was on that 1903 day, at the Royal Institution. An evening lecture was about to start. It was due to be presented by a young physicist, John Ambrose Fleming, and was to feature a demonstration of a new technology of the age: a long-range wireless communication system pioneered by the Italian radio engineer Guglielmo Marconi. The lecture was to include Fleming receiving a message sent by Marconi from his station in Cornwall. The aim was to showcase publicly for the first time that Morse code messages could be sent wirelessly over long distances, and more importantly, they could be sent securely. Not all went to plan, however.

Marconi was immensely proud of his wireless system. He dreamed of its contribution to the betterment of mankind, but as a shrewd businessman, he also knew of his invention’s value in financial terms, and the promise of security could only add to this. He boasted to all who would listen, and wrote to the St James Gazette in February 1903: “I can tune my instruments so that no other that is not similarly tuned can tap my messages”. The financial bounty that Marconi was set to earn would certainly come at the cost of the existing wired telegraph companies, who had sunk millions into land and sea cabling in order to allow messages to be sent around the world. As Marconi began to patent parts of his system, these telegraph companies realised that their long-term investments may be for nothing if a secure wireless technology had been created. One communication company decided to act and took the opportunity to employ a young telegraph enthusiast to test Marconi’s new unbreakable wireless system.

Neville Maskelyne was a British music hall magician who had already undertaken some telegraph experiments. He was keen to see whether Marconi’s system was truly as ground-breaking and secure, as he claimed. The Eastern Telegraph Company tasked Maskelyne, to set about the business of breaking into the secure communications. He started his task by building a 50-metre radio mast on the cliffs of Porthcurno to see if he could intercept Marconi’s company messages being sent to vessels at sea. He succeeded quite easily and soon realised that without tuned equipment it was relatively easy to intercept a signal without anyone knowing.

A few months later, back at the Ri, an expectant audience was waiting for the young Fleming to organise his equipment in the lecture theatre, when the apparatus suddenly began to tap out a message. To the audience, it sounded just like a rhythmic tapping noise, but to Fleming and his assistant, it was a clear message. And it wasn’t the one they were expecting.

At first, the message spelt out just one word repeated over and over: ‘Rats’, ‘Rats’, ‘Rats’. Then it changed to a poem accusing Marconi of "diddling the public” - there was a young fellow of Italy, who diddled the public quiet prettily (further lines followed). It was obvious to Fleming that the demonstration had been hacked.

The obscure message that had mysteriously arrived suddenly stopped shortly before Marconi’s signal from Cornwall arrived. However, the damage was done. If someone could interrupt the inventor of the apparatus while he was showcasing it to the public, then no message could be safe. Fleming was incensed at the intrusion on his friend’s breakthrough and wrote a strongly worded letter to the Times calling the act of hacking ‘scientific hooliganism’.

Desperate to know how and what had happened, Fleming appealed to readers of The Times to unmask the culprit responsible. This proved to be an unnecessary task as Maskelyne was quite happy to reveal his part, in his own letter to the Times four days later, justifying his act on the grounds that the public needed to know that there were flaws to this secure system.

It may have been an unintended ‘first’, but as a first nevertheless, Neville Maskelyne’s exposure of the flaws in Marconi’s wireless deserves its place in the litany of firsts witnessed by a public audience during a Discourses at the Royal Institution. The first announcement of the discovery of the Electron (when JJ Rutherford spoke for an hour without actually saying the word ‘electron’). The first announcement of photography, and of colour photography, the first demonstration of moving images and the first recording and playback of sound, to name but a few.

And after 200 years of firsts, Ri Discourses are the world’s longest-running series of science lectures for adults and still take place in our Theatre today. Visit our what’s on pages to discover upcoming Discourses and other Theatre talks where scientists and the public can come together to share their passion for science.