I have to admit I always get very excited about historical globes. Not only do they fall under my professional expertise but they were often silent witnesses to great ventures, great discoveries and great scientific projects. Globes were expensive, luxury, handmade objects, but in some cases owned by professionals who purposefully used them for navigation and astronomic calculations.

Globes have been created as visual representations of the physical characteristics of the Earth and sky for thousands of years. Terrestrial globes detail geographical features of the Earth. The oldest surviving terrestrial globe is the painted, end of 15th century Erdapfel by Martin Benheim, kept in a museum in Nurnberg. The literal translation of Erdapfel from German is ‘Earth apple’.

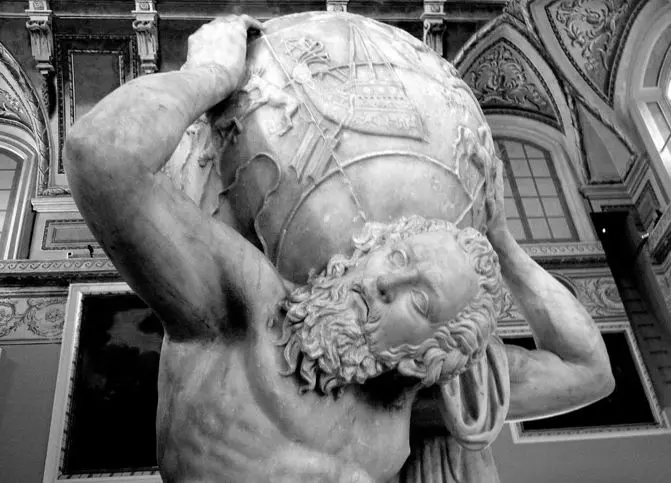

Celestial globes are spherical maps of the sky, small models of the visible heavens. The oldest known surviving ancient globe is the Farnese Atlas statue of Atlas (75 BC) carrying a celestial sphere on his shoulders. The second oldest surviving celestial globe is a brass sphere kept in the Louvre Museum, which comes from Isfahan, Iran, and dates back to 1144.

Just as with terrestrial and celestial explorations, artistic and scientific fascination with the moon appears constantly throughout the earlier centuries.Moon observations were often published in the form of detailed maps and many famous astronomers were also lunar cartographers. And while lunar cartography got an obvious boost as a result of the 20th century moon landings, there are some examples of old lunar globes dating to before the dawn of the 20th century. The very first ones were created in Great Britain during the 18th century.

As a paper conservator I have come across many terrestrial and celestial globes, as they were usually created in pairs. For me globes are beautiful but complex objects due to their nature. Their spheres are handmade of papier-mâché and polished plaster with printed gores (usually engravings from copper plates) pasted onto it. Very often these are hand coloured and varnished, and sometimes waxed and polished again. A variety of different materials with different properties within one object always makes for a conservation challenge. In other words, globes can be a conservation nightmare for the unexperienced restorer.

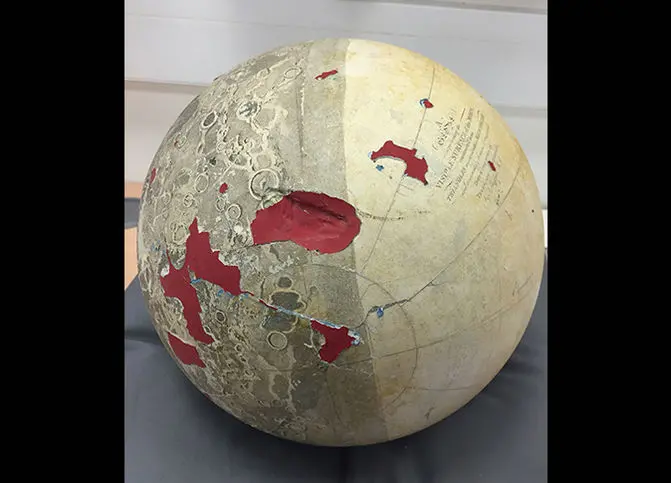

A couple of years ago I was very lucky to work on the Selenographia, a very rare lunar globe, one of the dozen exemplars present in national and private collections worldwide. Selenographia is the earliest surviving printed lunar globe1. The chance that a paper conservator will work on such a rare object even once in a lifetime is pretty small. Since this experience my expectations towards globes are always high.

This is partly why, when our curator Charlotte New showed me a modest box from the Ri collection with something that looked more like an oversized Christmas tree decoration (the result of various mysterious 20th century alterations) I just ignored it, making a kind of "I will think about it tomorrow" remark.

Then after couple of weeks being a dutiful person (sic!) I leaned over this box filled with the 12 inch sphere. Despite its patchy appearance it looked surprisingly familiar. I closed my eyes. Opened them and looked again. I did not scream only because holding in emotions is an essential part of my professional skills.

There it was, decorated with strange blue and red infills - The Selenographia, Globe of the Moon by John Russell, published in London in 1794. Without its stand, with some strangely painted fixings, slightly crushed (this is not so surprising with a historical globe I must admit, they are very prone to such injuries). Was it possible that I held in my hands a second Selenographia?

After examining the globe’s surface under a microscope and comparing it with my old documentation, I realised that this is not a mirage or a forgery - this is the original lunar sphere from Russell’s Globe of the Moon.

What is so amazing and rare about this scientific apparatus that it is part of the Ri’s collection? Literature usually quotes that about a dozen Selenographias still exist. There are examples of complete Selenographias in the Oxford Museum of Science, Science Museum London, National Maritime Museum, and The Royal Observatory in Madrid. Two exemplars furnished with wooden stands are in the Birmingham Museum and the Science Museum in London. Another Selenographia with complete apparatus was sold by Bonham’s in 2012. It is believed that there are perhaps two more in private collections.

But for me the most interesting thing about this globe besides its rarity, is its creator. It was not a scientist (in today’s meaning of the word) who created the best early maps of the moon and the Selenographia globe amongst them. It was a popular and fashionable portrait artist who drew portraits and miniatures in pastel.

John Russell, R.A. (1745-1806) created about 800 portraits of the great figures of British religion, art and science of the Enlightenment.

He was not satisfied, however, with his successful artistic career and he decided to make his own contribution to science. This contribution ‘consisted of drawing the largest and most accurate picture of the moon produced up to that time; in making a mechanical moon globe bearing an engraved moon map, the ‘Selenographia’; in designing a relief globe of the moon; and in engraving a contrasted pair of full-moon maps which he called ‘Lunar planispheres’.

His fascination with the moon started when he was a young man and had a chance to look at the moon through a telescope. He was immensely struck by its beauty and clearness. His letters confirm that he had an access to the very luxurious and expensive Hevelius’s atlas3 and to Cassini’s lunar map. Inspired by works of these famous lunar cartographers, Russell decided to try to depict the moon highlighting its inherent dark and light parts and to look at it from a scientific and artistic point of view to fully imitate its beauty. The Selenographia was a result of 18 years of telescopic observations, study and micrometric calculations - from time to time Russell was turning to his scientific friends for help in the latter.

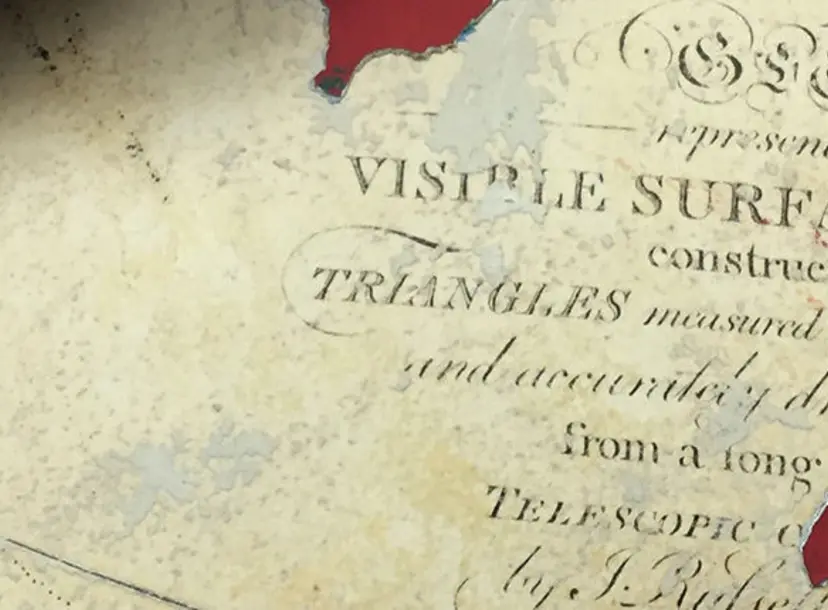

In his own words: "The Selenographia consists of a Globe, on which are expressed the spots which appear on the moon’s visible surface, accurately taken by a micrometre from the moon itself, and transferred to a globe. The papers which cover this globe are carefully engraved from the original drawings, made by a long series of very minute observations; the lunar mountains being attended to, and expressed with great exactness."3

The lunar sphere was meant to be either mounted onto a sophisticated brass stand or furnished with a simpler mahogany stand. The globes were made to order and accompanied by a spare set of engraved gores and calottes, and a booklet: "A description of the selenographia: an apparatus for exhibiting the phenomena of the moon. Together with an account of some of the purposes which it may be applied to".

For me it is the beginning of an exciting project: we have to find out how and when the globe was acquired by the Royal Institution. Which scientist used it or who donated it as a gift? How long it has been used for teaching purposes? Perhaps there is another story bound with this object and maybe it was used during one of the Christmas lectures? How do we bring it back to its glory?

For now I am off to have a look at another box Charlotte showed me earlier this week. Who knows what treasures may still lie hidden?

References

1 Sylvia Sumira, The art and history of globes. The British Library, 2014, pp.174-177

2 W.F. Ryan, John Russell, R.A., and early lunar mapping. The Smithsonian Journal of History, Volume 1, 1966, pp.27-48

3 Hevelius, Johannes (1611-1687). Selenographia: sive Lunae descriptio; atque Accurata, Tam Macularum eius, addita est, lentes expoliendi nova ratio. Danzig: Andreas Hünefeld for the author, 1647

4 John Russel, A description of the selenographia: an apparatus for exhibiting the phenomena of the moon. Together with an account of some of the purposes which it may be applied to. By John Russel, R.A., Eighteenth Century Online Print editions. Reproduction from British Library