Calls for free meals to be made available to all children in England are growing louder, while an increasing number of families turn to foodbanks to cope with rising prices and high energy bills. We may be forgiven for thinking we’re living in the midst of a novel by Charles Dickens. But hope can be found, now as it was then, in people’s willingness to help – as we explore an unlikely link between a Victorian champion of education, one of the world’s most famous scientists, and an English star of the Qatar World Cup.

Many families in the UK are struggling with the current cost of living crisis. Some help can be found from supermarket vouchers schemes which are available during school holidays to those children eligible for free school meals. These exist in a large part due to a high-profile campaign by footballer Marcus Rashford in 2020 which called for free school meal benefits to be extended into the holidays.

Two years on, Rashford was back in the headlines as England’s joint top-scorer during their appearance at the Qatar World Cup. And free school meals continue to be a hot topic with the #FreeSchoolMealsForAll campaign calling for the scheme to be extended to all primary school children in England, as Scotland and Wales have already promised to do.

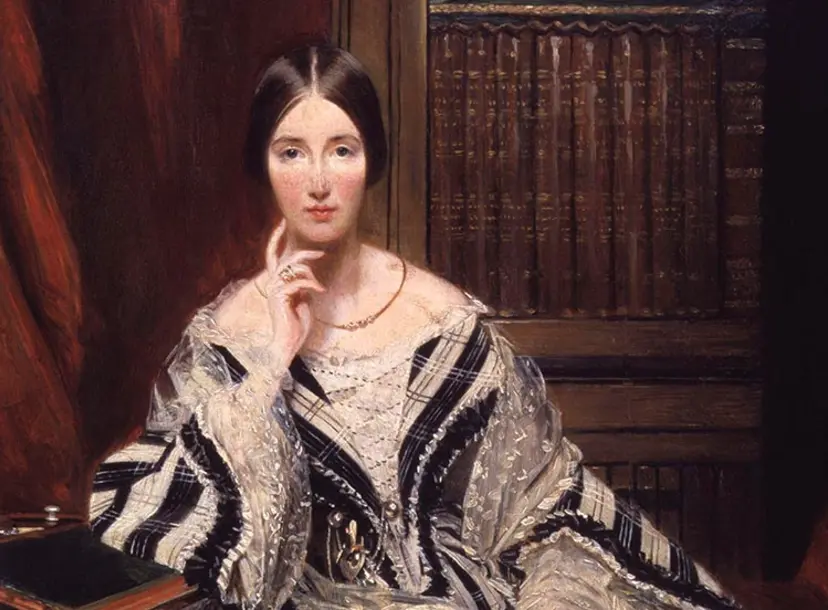

A celebrity figure like Rashford stepping in to campaign for aid to disadvantaged children is nothing new. And, sadly, neither is the need for help. With the Child Poverty Action Group estimating that 800,000 children in England are in need of free school meals but do not meet the eligibility criteria, you could be forgiven for comparing the current state of child food poverty to the famously austere Victorian era. The images of poor houses and destitute orphanages are probably clearest to many of us from the works of Charles Dickens, but the famous novelist did not simply portray the plights of the poor in fiction; he was dedicated to helping in reality. In particular, Dickens took a strong interest in the importance of education, a subject which he regularly discussed with his friend Angela Burdett-Coutts, considered "the wealthiest woman in England" after Queen Victoria.

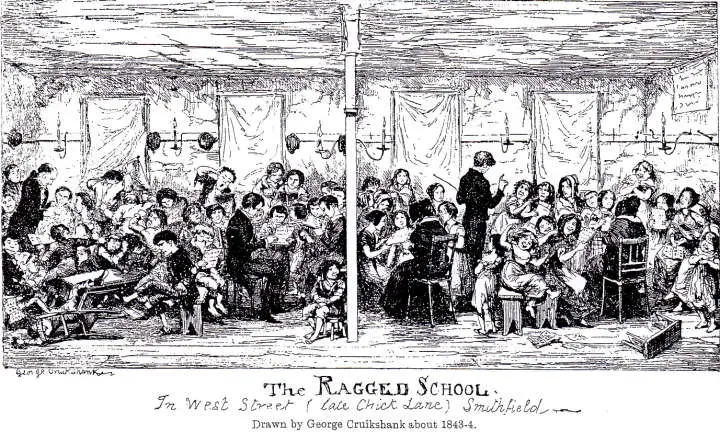

Although largely forgotten today, Burdett-Coutts was a prolific philanthropist in the Victorian era. Having inherited the fortune of her grandfather, Thomas Coutts of Coutts bank, at the age of 23, Burdett-Coutts spent her life using this money to support those living in poverty, in particular children, engaging with many projects that were forward-thinking for the time but are staples of the charity landscape today. For example, she was involved in the establishment of the London Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children – better known by its current name of the NSPCC. Alongside Dickens, Burdett-Coutts was also a staunch supporter of London’s ragged schools: charitable organisations providing free schooling to disadvantaged children.

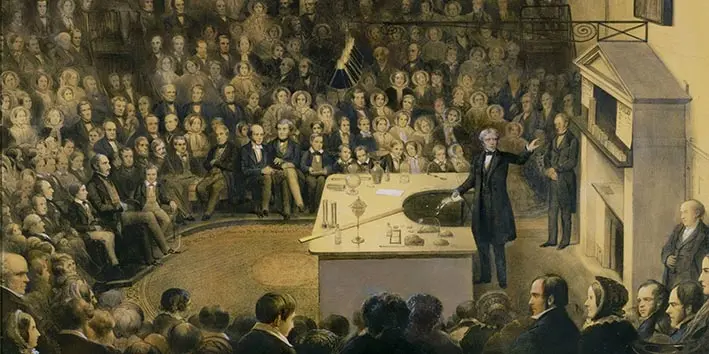

A belief in the importance of education and its availability to all classes united Burdett-Coutts not only with Dickens, but another celebrated figure of the Victorian age, the scientist Michael Faraday. Faraday was Director of the Laboratory here at the Royal Institutio from 1825–1867. Ri Members were the first to know about major scientific advances such as the development of the electric motor (by Faraday himself), the discovery of greenhouse gases, and the process of photography, all of which were first announced in our Theatre. Today, records of those members are preserved in the archives, including the numerous membership applications that had to be signed by at least four pre-existing members to be approved. Burdett-Coutts’ application is among them (unlike many other institutions at the time, we have always allowed female members), approved in 1847 and signed by Faraday himself.

In signing these forms, members were recommending the applicant to the Royal Institution on the basis of ‘personal acquaintance’ – so Faraday’s support of Burdett-Coutts indicates a friendship between the two. This is also apparent in the records of their letters, included in Professor Frank James’ meticulous multi-volume collection of Faraday’s correspondence. Alongside details of social engagements and enquiries after the health of loved ones, the two write to each other enthusiastically on the topic of education. On one occasion, Faraday writes that when ‘talking with Madame De la Rive this morning about education I spoke to her of your schools’. Burdett-Coutts also shares with Faraday her strong feelings about ‘perseverance under difficulty in the acquirement of knowledge, from a love of the thing itself, and not as a means of getting on in life which is so insistently put forward by educationalists’.

Faraday, like Dickens and Burdett-Coutts, was dedicated to the education of children in theory and in practice. He established the Christmas Lectures in 1825, when formal education for children was scarce, and these public talks designed to introduce children to science in an engaging manner, have continued annually ever since, stopping only during the Second World War. The most recent lectures, broadcast on BBC Four were given by the world-leading forensic anthropologist Professor Dame Sue Black.

The legacy of all three of these Victorian figures extends into the present day, both through the organisations they worked with and in the spirit of those, like Marcus Rashford, who continue to campaign for better conditions for our children. And one thing that has definitely improved in the twenty-first century is the opportunity for more people to make their voices heard. You no longer need to be a world-famous writer or scientist, or the second wealthiest woman in England to make a difference. Campaigns such as Rashford’s show that celebrity support is still a powerful tool, but it is bolstered now by an outpouring of public sentiment on social media and through online petitions – sentiment which was central to the success of Rashford’s campaign in 2020 and may prove to be so again to secure #FreeSchoolMealsForAll. We can imagine that Dickens, Burdett-Coutts and Faraday would have wholeheartedly supported this campaign to improve the lives of children across England, and see their legacy flourishing in the work of all those who support it.

About the author

Megan Stephens is an AHRC-funded PhD student researching representations of death in contemporary media. She has recently completed a three-month internship with us, applying her research skills to the archives and history.