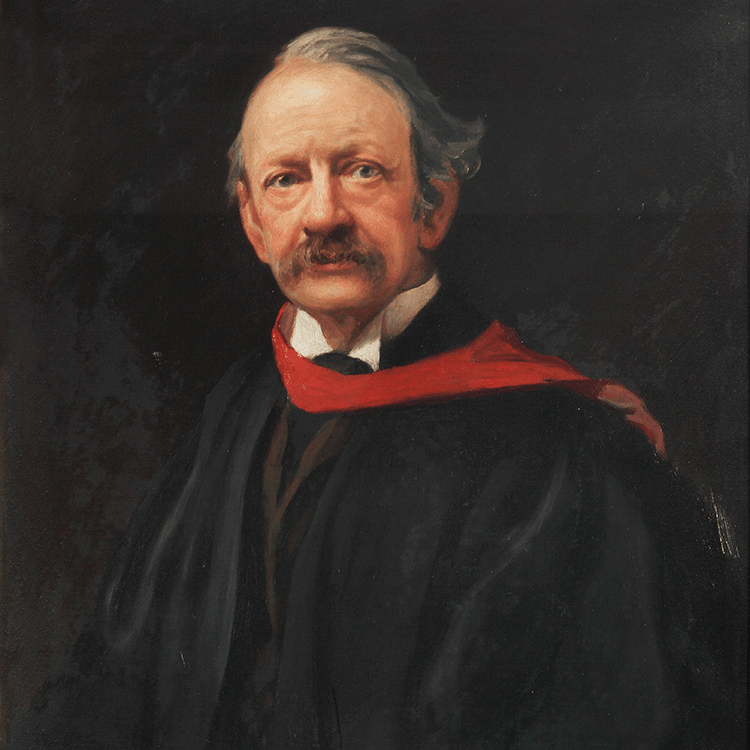

JJ Thomson, while familiar to scientists, is not necessarily a name most people would recognise; however, anyone who has undertaken any science at school will have heard of an electron.

It is Thomson we have to thank for discovering this fundamental breakthrough in science and announcing his discovery to the world during a lecture here at the Royal Institution in 1897.

What is an electron?

The technical definition is:

"An electron is a stable subatomic particle with a negative electrical charge. Unlike protons and neutrons, electrons are not constructed from even smaller components."

As a non-scientist this definition is something I have heard before but must confess is not something that means a great deal to me. It is an explanation in its basic form but doesn’t convey really what an electron is or what the impact of its discovery made

John Dalton's atomic theory

Prior to 1897, scientists had hypothesised about the makeup of the universe at the atomic and subatomic level but had not been able to prove any theories. The atom had been known about for many years.

In 1808, chemist John Dalton developed an argument that led to a realisation: that perhaps all matter, the things or objects that make up the universe are made of tiny, little bits.

These are fundamental and indivisible bits and named after the ancient Greek words ‘a’ meaning not and ‘tomos’ meaning cut therefore ‘atomos’ or uncuttable. Atoms.

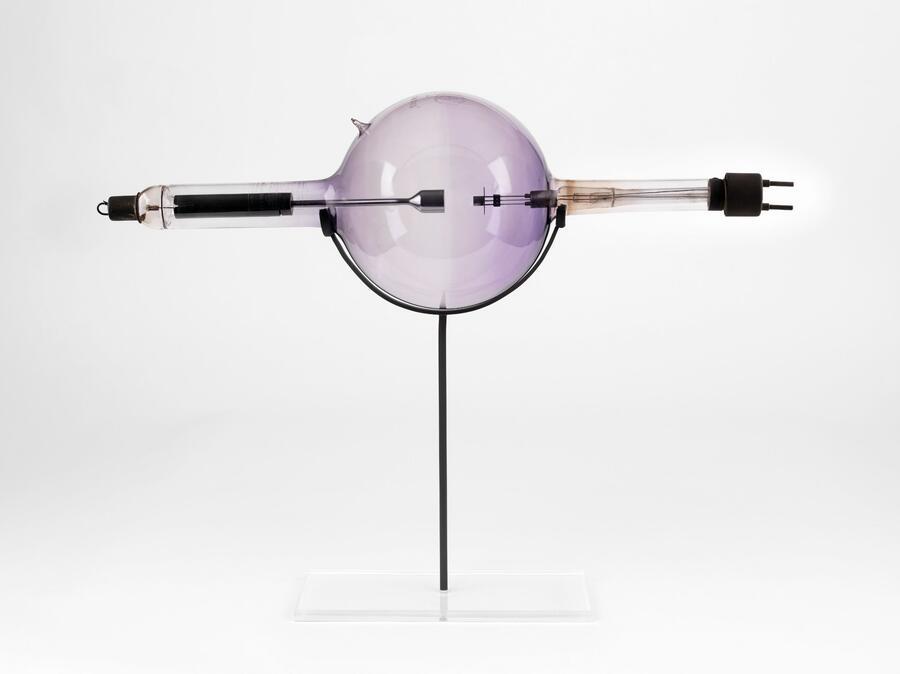

JJ Thomson's cathode ray tube experiments

Thomson, a highly respected theoretical physics professor at Cambridge University, undertook a series of experiments designed to study the nature of electric discharge in a high-vacuum cathode-ray tube – he was attempting to solve a long-standing controversy regarding the nature of cathode rays, which occur when an electric current is driven through a vessel from which most of the air or other gas has been pumped out.

This was something that many scientists were investigating at the time. It was Thomson that made the breakthrough however, concluding through his experimentation that particles making up the rays were 1,000 times lighter than the lightest atom, proving that something smaller than atoms existed.

Thomson likened the composition of atoms to plum pudding, with negatively-charged ‘corpuscles’ dotted throughout a positively charged field.

G Johnstone Stoney coins the term 'electron'

Thomson explained within his lecture all of his experiments and the results, never mentioning the word electron but instead sticking to corpuscles to explain these tiny particles in the same terms as biological cells (corpuscles are a minute body or cell in an organism).

Such would they have remained if not for the term 'electron' coined by G Johnstone Stoney who in 1891 denoted the unit of charge found in experiments that passed electrical current through chemicals.

It was then in 1897 after Thomson’s publication of his research that Irish physicist George Francis Fitzgerald suggested that the term be applied to Thomson's research instead of corpuscles to better describe these newly discovered subatomic particles.

JJ Thomson and the Royal Institution

Thomson had a long-standing relationship with the Royal Institution during his long academic career in Cambridge, lecturing many times on the development of physics through Discourses and educational lectures to all ages.

Thomson was a great friend of Sir William Henry Bragg and Sir William Lawrence Bragg, who jointly won the Nobel Prize in 1915 for the development of x-ray crystallography, and who were both former Director’s of the Royal Institution.

JJ Thomson's Nobel Prize

Thomson received the Nobel Prize for his work in Physics in 1906 and was knighted in 1908. The studies of nuclear organisation that continue even to this day and the further identification of elementary particles have all followed the accomplishments of Thomson and his discovery in 1897.