Lecture 1 – A is for atoms

From the 1993 lecture programme:

Our five senses only reveal a small part of the large variety in the Universe. We cannot see molecules unaided (though our nose can smell particles much smaller than our eyes can see) and we only respond to the rainbow of colours – a mere octave in the infinite range of the electromagnetic spectrum.

If we had a bee’s eyes we could see in the ultraviolet; we can feel infrared radiation as heat and occasionally one hears of people picking up radio signals in their dental fillings. Our ancestor's eyes were developed to guard against attacks by dangerous animals; it was not important for them to see distant radio galaxies. Today, by means of infrared cameras, we watch for human prowlers in the dark and can look deep into the Universe, revealing much more than shows up in the tiny range of visible light.

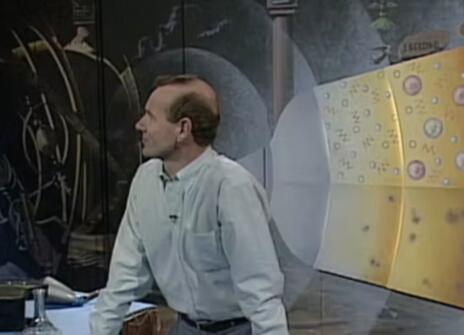

An aim of the lectures is to open up a spectrum beyond the rainbow, towards smaller wavelengths that can see smaller things. Even with a powerful optical microscope we cannot resolve individual molecules. X-rays can resolve distances similar to the separation between molecules in a regular crystal, as in the discovery of the structure of DNA, but do not reveal the individual molecules.

Electrons, which are present in everything, provide access to distances smaller than X-rays can reveal. Electron microscopes in the laboratory can provide pictures of molecules, even of atoms. With a two-mile long electron microscope, we can even look deep inside an atomic nucleus.

About the 1993 CHRISTMAS LECTURES

In our 1993 CHRISTMAS LECTURES, particle physicist Frank Close OBE looks at how our understanding of particle physics developed over the 20th century.

From the 1993 Lecture programme:

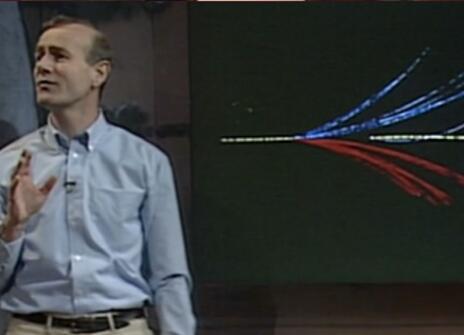

The lectures will trace a hundred years of discovery and invention, culminating with a look into the crystal ball towards the next century. The developing story begins in 1893, when the Royal Institution lecturer inhabits a world ignorant of radioactivity, electrons and the working of atoms, knowing nothing of how stars shine, nor of galaxies let alone that they are rushing outwards from a primeval big bang.

Even so, scientists were confident that they were on the brink of describing all basic natural phenomena. Fundamental discoveries at the turn of the century changed all that. Hints that “all was not well” turned out to be true and revolutionary rather than requiring tinkering with a few ideas.

A century later, in 1993, one hears talk of a 'Theory of Everything' and there is debate as to whether we can 'know the mind of God'. Yet even now there are hints that 'all is not well'. The lectures will bring us to the current frontier and try to learn from the experiences of the intervening century of discovery and controversy.

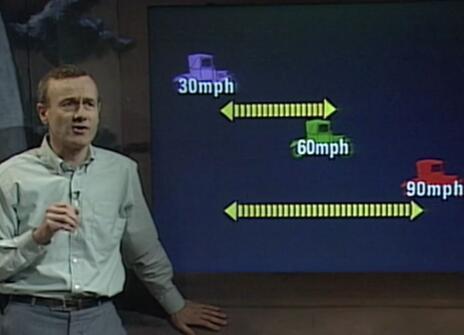

The theme will show how discoveries of natural phenomena provide new tools that, in turn, open up new areas of research leading to further insights, innovation and technologies. The developments feedback, creating new opportunities which often are far removed from the original discovery. The net result is that we are continually extending and deepening our experiences of Nature beyond those accessible to our five senses.

Our five senses reveal the beauty of the everyday world, enabling us to look out to nearby stars, to focus on objects as small as the width of a human hair and to react to events as brief as 1/25th of a second. Many other animals have sharper senses than ours but our ingenuity and inventiveness in effect extend our senses with telescopes, microscopes and other sophisticated tools. Thus it is our 'sixth sense' that expands our watch on the Universe, reveals images deep within individual atoms and discovers Nature at work on timescales of less than a microsecond.

Telescopes on satellites above the atmosphere capture light that was born when the galaxies first formed. Experiments in high energy particle accelerators on Earth teach us how to decode these messages that reveal our origins: we are looking back to (nearly) the Big Bang.

At another extreme we can photograph and display the entire life of a single subatomic particle lasting a mere thousand millionth of a second – an essential part of Nature’s scheme but hidden from our five senses. As hieroglyphics contained the secrets of the Pharaohs, so do these modern pictographs from CERN begin to reveal the story of creation. Not only can we see how the stuff of the present Universe was formed, we also have clues to its possible fate.